“You didn’t tear your ACL because you had a girlfriend.” Felix’s words from weeks ago repeat in my head as I take the arms of two medics who are ushering me off the court with an efficiency I recognize from the last time I ate shit this bad. How could this be happening again? I let myself get all caught up. And now I’m out. My feet squeak across the waxy floor as they hurry me along.

Fuck.

Why is this my first thought? Why am I blaming her? There has to be something else, something more logical I can wrap my head around.

My head. I spin back into focus as the pain starts to skewer through my forehead and burst through my skull.

“I think I’m gonna…”

“Here, right here,” one of the medics, whose face is a bit of a blurry shape at the moment but definitely radiating big dyke energy (I spot a carabiner on her left hip belt buckle), hands me a sterile-blue vomit basin. I realize we are in the medical treatment room before I lose it all over the plastic, kidney-shaped bin. My grandmother always called puking “performing” — maybe to make it sound more grand.

She’d stay home with me from school when I had the flu. I used to clench my mouth and shake my head every time I knew I was about to puke. “It’s time for your next performance,” she’d say to me, as I shook my head, gripping the toilet, unwilling to let the bile and waste make their way to my throat and mouth. “Come on, let go.”

And once I did, the twisty feelings in my stomach would always release. I’d feel free and better, and I’d also always get rewarded with some flat Sprite, my grandmother’s go-to antidote for even the smallest sniffle.

I wish I had some flat Sprite now. After I finish my performance, Big Dyke-Energy Medic takes my right hand, which was previously gripping that puke bucket like it was the ball during crunch time in the fourth quarter. “Obviously, we are going to examine you for a concussion now, though that kind of seems like the clear culprit here,” she says, adding a sympathetic light chuckle as she hears my drawn-out groan.

Dr. Beech walks in to tell me that I, indeed, have a Grade 2 concussion (after playing as long as I have, I’m pretty used to neurological exams for head trauma, but they never get more fun). She asks me the question that almost makes me puke again. “Do you want any visitors now?”

I know Felix is right outside the door. She’s not covering the game, but to anyone else she probably looks like a concerned journalist; even though we’ve moved well past reporter-subject mode, she tends to keep Serious Reporter face plastered on when she’s in the basketball arena.

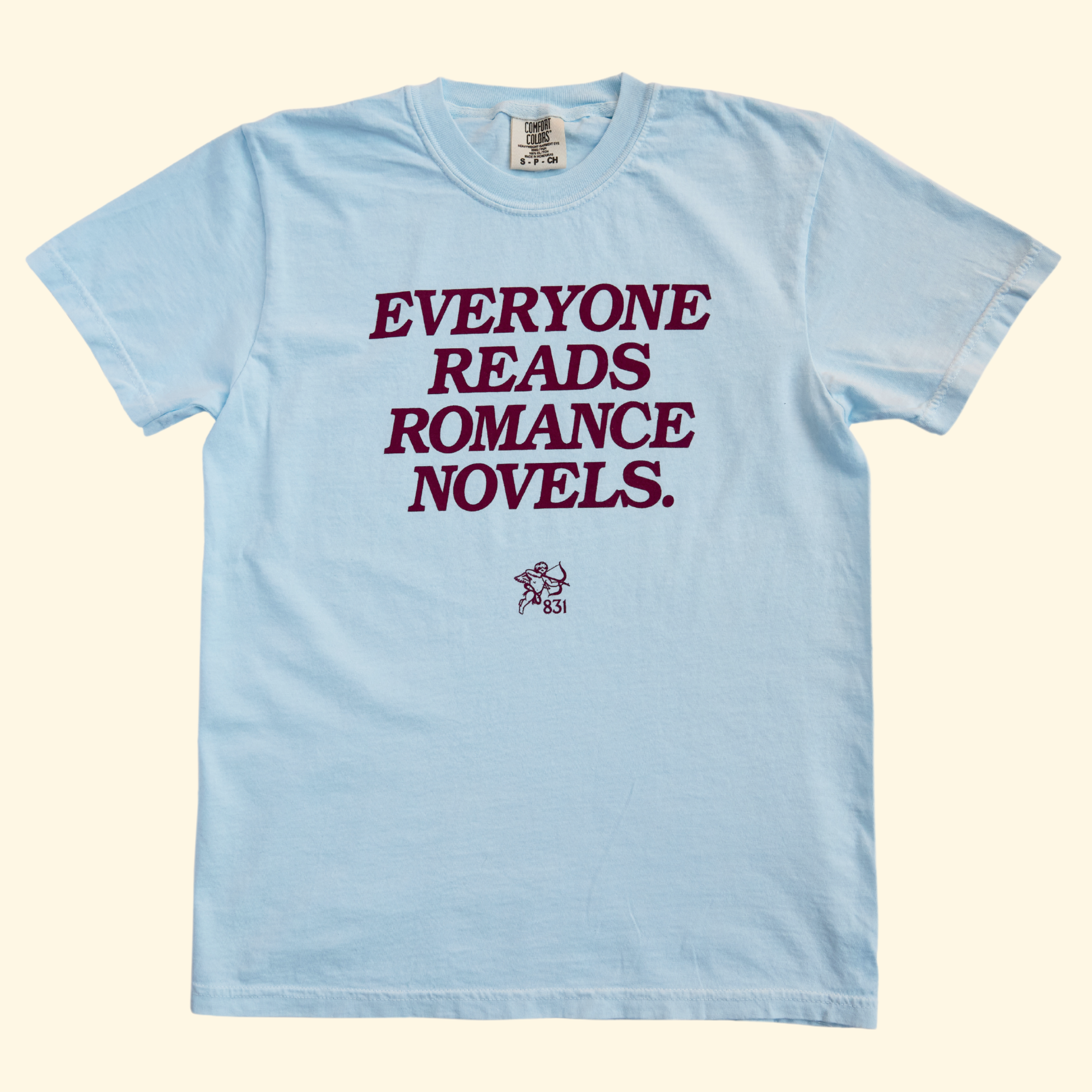

But these days, I know better. These days, though, she can put on that Reporter Face, but all I can think about is what she said to me before the game: “I want to smell you on me all night.” I’d gotten dizzier than I feel right now when she said that. She was wearing my white t-shirt, and you would have thought she had shown up in nothing at all; my legs buckled when I saw her in it.

She instantly shot me back to that first night we spent together, to the way the curve of her hip felt as I leaned into her, kissing her slow and deep for the first time. To the way she let me know she was in charge, taking my hand off her body, and brought my fingers to her mouth, then down her pants and onto her — I’ll never forget it — wet and inviting clit. She took control and I let her. I let her tell me what she wanted, and was, for once, out of my head and totally in my body.

“No one gets me as soaked as you do. As watching you does,” she’d said to me, and my whole body had lit up with the desire of only wanting to please her, to make her even more wet, to want me more. I’d asked her to say my name when she came. I wanted to hear it on her lips, in her groan, in a tight and desperate cry, as I filled her up and made her shake against the pressure of me inside her.

And she had. She’d said my name. Over and over as she came, in a tight, desperate tone. Hearing it from her: Natalie, Natalie, Natalie — and not one of the many nicknames I hear echoed across a basketball court on any given game night — felt more right than I’d ever heard it before. In one of the corny rom-coms I secretly love; OK, I know exactly which one — Sleepless in Seattle — Tom Hanks says the first time he helped his wife out of a car is when he knew he was going to marry her. “I knew it. I knew it the very first time I touched her. It was like coming home, only to no home I’d ever known.”

I’d be kidding myself if I didn’t think of that scene when Felix said my name that night. It was like a corny (and maybe a little raunchy) rom-com. It was like coming home.

But just as Rosie O’Donnell tells Meg Ryan, “That’s your problem. You don’t want to be in love; you want to be in love in a movie.” Maybe that is my problem. That, and the fact that I have watched freaking Sleepless in Seattle way too many times. If I’m being really honest, I do want to be in love in a movie. I want the kind of magic that I feel when I’m on the court. I want it all the time. But I can’t have both.

Obviously. My head throbs once more as I finally answer Dr. Beech: “Sure, can you send in Jennifer Felix? I’m guessing she’s right outside.”

As she leaves the room, I shudder as I turn my body away from the door, sticking one of my legs out from under the scratchy white sheets on the bed. I let the other shake with all the excess energy still zipping through my body since the game. I knew this conversation was coming. I hear the door open and shut, hear her walk toward me.

“Is your headache bad?” she asks.

Nothing is as bad as hearing your voice right now and knowing what I’m about to do, I think. I’d known since the moment my head hit the ground. I can’t talk myself out of it.

“They gave me some Aspirin,” I reply simply, trying to give off the impression that I am totally fine and not about to break apart completely.

She doesn’t seem to buy it. I still haven’t looked at her, keeping my eyes toward a clear cabinet stocked full of Kinesio tape and pre-wrap.

“How are you feeling?”

I finally force myself to turn back toward the entrance of the room and toward her.

She reaches out a hand, but doesn’t really touch me. She just lets it float there, like she’s not sure if she should make contact.

“Please, don’t touch me,” I hear myself say. God. Why am I such a dick? I can’t even let her touch me, comfort me? I start to let myself lean into her and apologize.

But I steady myself. I let my voice get as monotone as it can, when I say, “Whatever we’ve been doing, it’s obviously over.”

I want to stop, I want to tell her to ignore everything I say, to tell me to shut up, to tell me I don’t know what I’m talking about. I want her to take me back to our hotel room and bury her fist deep inside me, until I can’t breathe, until I can’t say another word about ending this. I want her to make me forget who I am. Forget the game, forget what just happened. Forget that I have been sidelined during the playoffs.

But instead, I continue: “You can stay in the hotel room tonight, but I’m going to find somewhere else to stay.”

I look at her. Her usually flushed cheeks — how she usually looks when she’s trying to make a point or impress me with her newfound, impressive knowledge of the game — are completely drained of their usual luster.

“It’s not,” she says.

What’s not? I think, having already purposefully erased every painful thing that’s already been released from my chest.

“It’s not obviously over,” she chokes out, sensing my confusion. “You can’t just end things like this.”

But I just did. Please don’t make me explain myself. Please. I am the worst person to ever exist. Please don’t make me defend this.

“Of course I can,” I will myself to say flatly, as I continue to let my leg keep the beat of my own nauseating anxiety. I keep my face still and say the thing I want her to believe, because I do mean it: “It’s not your fault.”

And then I say the thing I can’t stop thinking: “This was incredibly stupid of me. I should have known something like this would happen.”

The next few moments blur out. My head pounds harder as I try to focus, but I don’t hear her as she’s speaking. I just know I need to keep making my case, I have to stay the course.

“I couldn’t stop thinking about you wearing my stupid fucking shirt on the court, and I hurt myself again,” I say, somehow still managing to shift the blame to her.

Felix twists her mouth into a knot of frustration and rage as her eyes well. Looking at her makes me want to launch myself off this bed and run right through the door. I want this to be over. I know if we keep talking she’ll just say all the things I’ve already thought, all the logical reasons I shouldn’t do this.

But I don’t move. I just let her talk.

“You didn’t hurt yourself because you like me, it was just bad luck, bad timing.”

Damn it. Stop it. Don’t talk me out of this. I already did it. I can’t go back.

So, I say it. I say the worst possible thought that comes to mind, hoping it will be the final cut to bleed this whole thing dry.

“Basketball is the most important thing to me, much more important than whatever dumb shit we were doing together.” There. That should do it. I shake my head to drive home my point, ignoring its continued pulsating. “You should leave.”

“Hey, Dr. Beech? Can I switch out my visitors now?” I know Weesie is just outside the door, and while I know I’m going to get a lecture from my teammate for what I’d just done, I prefer that to watching Felix’s face oscillate between heartbreak and fury. She turns away from me with a slight jerk, as Dr. Beech ushers her out the door.

As soon as it clicks shut, the tremors in my leg travel to the rest of my body. I grab the basin and hurl my guts out. This time, I know for sure it has nothing to do with my concussion.

I get back to my apartment around 8 p.m., my stomach still heavy from team dinner at our favorite Lebanese restaurant in WeHo. Jada had insisted we order several rounds of babaganoush for the table, and I’d dipped more warm pita bread than I’d usually like to have the night before a game. Not that I had any issue with bread. But I can feel the weight of it settle into my stomach as I strip off my Lights sweats and turn on the hot water in the shower.

On second thought, this sinking feeling is probably not from delicious carbs. This feeling hasn’t left my stomach since after game 1 and the medical room. Not since I’d leveled Felix with words that had woken me up each night since I’d said them.

My stomach tightens as the warm water rolls off my shoulders. Game 2 is tomorrow. I’d gotten cleared after all; it turns out the puking had more to do with what happened after I smacked my head on the floor than the head-smack itself. My concussion wasn’t nearly as bad as we thought, and Dr. Beech has ensured that my head is fine.

Physically, maybe.

I dry off and settle into my flannel pants and reach for a soft t-shirt in the second drawer of my dresser Then my eyes dart to my dirty clothes hamper in my closet. At the top of the folded stack was the t-shirt Felix had borrowed.

I hadn’t even realized that I’d folded it instead of chucking it in my dirty-clothes bin when I unpacked. I’d found it on the handle of my hotel room door the morning after. I’d stayed in Weesie’s room to hold to my end of the deal, letting Felix have my room. But the shirt seemed like a clear message that she did not want to enter my space, even for a second.

Now, I take it out of the drawer and slip it on. I decide not to think about why wearing it makes me feel better than I have in two days. I flop onto my bed, grab my phone, and suddenly, I’m searching for a name I haven’t called or texted in a year.

“Hey, kid,” Allison Altman’s voice comes through the phone after the second ring, and I can’t help but break into a smile when I hear it. She’s only two years older than me, but she always loved to remind me of that. I tried not to let on, but I always liked it; it made me feel taken care of, special.

“Hey, Alli. How’s retirement treating you?” I flinch at the lame cliché she’s probably hearing from every family member, friend, and reporter in her life.

“Oh, you know, I never stay down for long,” she says. “I’ve got a couple broadcast deals in the works, doing some commentary next season. I can’t stay away from the game.”

“Yeah, I get that…” I trail off.

“Natty? You okay? Not to be an asshole, but it’s not like we talk a lot since things ended between us. Like, I mean, I’m fine about it now. But you haven’t exactly called me for a chat in a while. I saw your fall the other night. Are you feeling alright?”

I sigh into the phone, fiddling with the fringe on the blanket over my knees. “Yes, I’m fine. I’m cleared to play tomorrow. I called because, well… I have to ask you something… What’s wrong with me?”

She laughs out a response: “What?”

“I mean, like, when I broke up with you. I convinced myself that you were a distraction. When we played on the court together the night of my ACL injury, all I could think about was you and how much I wanted to go home with you after the game. And then I fucked up and I was out for the rest of the season. You know all this.”

I listen for a response, but she’s silent, waiting for me to go on.

“And, sorry if this is weird, but I may be falling for someone new. And I may have just ended things with her because I thought I had crossed the line, let myself lose focus.”

This time I stop and wait for her to say something.

“Natty. Do you really believe this girl is to blame for you going down in a spirited game? Do you really believe I was to blame for your knee injury?

I breathe out again, long and slow, as she says more.

“We both know how locked in you are on the court. We also both know that shit happens. Nothing is wrong with you. Except that you’ve invented these rules to protect yourself from being with someone.”

I want to say something, but my throat feels like it’s about to close up. I let her continue.

“Let me ask you this: How do you feel when you’re on the court, knowing she’s watching you?”

I reply without having to think: “Like a goddamn hero. I love knowing she’s there.”

“Let me ask you another question. Do you want her there tomorrow?”

I start to simultaneously sob and laugh into the phone, the word “yes” suddenly not feeling big enough.

“Okay, I think I know the answer,” Alli says. “Now, a third question: Do you want to watch Notting Hill with me?”

Alli and I had started out as friends in college, where we’d discovered our mutual obsession with rom-coms. I wipe my eyes and chuckle. “Obviously. Where is it?”

“Netflix, but I’m actually just at the end; your favorite part. The press conference where Hugh Grant wins back Julia Roberts by pretending to be the reporter from Horse & Hound.”

As I flip to Alli’s exact place in the movie, a plan starts to formulate in my head.

Game 2. I’m flying. We manage to pull a win over Liberty. The entire time, I’m sinking shots and running screens for Jada and watching her score point after point, I’m in the game. But I’m also thinking about what I know I’m going to do the second this game is over. “I was playing inspired,” I tell a sideline reporter as sweat steadily drips into my eyes. And I was. I’d just wanted to prove to myself I could kill it on the court tonight before I enacted the next phase of my plan.

After I emerge from the locker room and as soon as I can work it out with Ashley — who should be a matchmaker if she ever wants to give up PR — I secure a ticket in the friends-and-family section for game 3 tomorrow night.

I take a screenshot and text Felix: “Please?”